Lactase insufficiency due to primary or secondary reasons results in clinical manifestation. The severity of the condition varies from person to person. Lactose is in dairy products, milk products, and mammalian milk. It is also occasionally named lactose malabsorption.

Lactase deficiency is the most standard kind of disaccharidase deficiency. Enzyme levels peak shortly after birth and decline subsequently despite continued lactose consumption. However, in the animal world, non-human mammals typically lose the capability to digest lactose into its elements once they reach adulthood.

What is Lactose?

Lactose belongs to the group of carbohydrates and is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose molecules. It is also called milk sugar due to its origin. The sweetness of lactose is lower than that of glucose or sucrose. This sugar is a colorless solid and dissolves well in water.

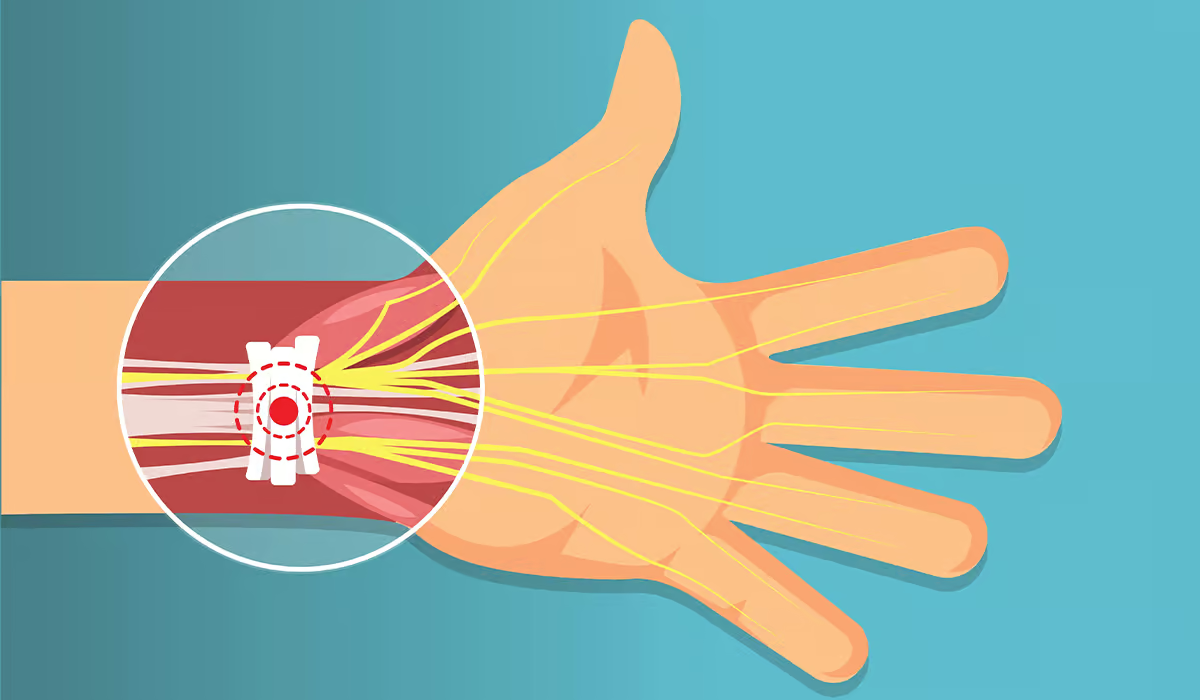

In the small intestine (more precisely – in the brush border of the mucous membrane), the enzyme lactase is present, which enables the breakdown of lactose into simple sugars – glucose and galactose. Thanks to this, they can be absorbed and used by the body.

Lactase activity decreases gradually with age. It is most common in newborns and breastfeeding infants. It also depends on other factors such as intestinal transit time, peristaltic movements, and quantitative and qualitative composition of intestinal microflora.

Lactose intolerance may result from primary, secondary, or congenital enzyme lactase deficiency. It causes the lack or insufficient digestion of lactose, leading to impaired absorption and an increased osmotic load in the intestine, which in turn increases the water content in it and leads to diarrhea.

Unabsorbed lactose goes to the large intestine, where it is then digested by bacteria, which produces hydrocarbons, carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen and consequently leads to troublesome gastrointestinal problems.

Is Lactose Intolerance the Same as Milk Intolerance?

Although in common parlance, milk allergy and lactose intolerance are sometimes confused or considered to be the same disease, they are two separate diseases. Although the straightforward reason for the symptoms of both conditions is the consumption of milk and milk products, each is answerable for a different element and a distinct response of the organism.

Cow’s milk contains several groups of nutrients: proteins, such as casein or whey, sugars, i.e. carbohydrates, including lactose – a disaccharide composed of a combination of glucose and galactose, as well as fats, vitamins, trace elements, and water.

The symptoms of milk allergy (commonly called “protein disorder”) are caused by milk proteins, which the body that is allergic to them treats as an allergen. In answer to contact with one of the milk proteins, an irregular resistant reaction develops, including the construction of antibodies produced against this protein, activation of Th2 lymphocytes and other cells of the immune system, and their release of histamine.

As a result of the intense immune reaction and the action of histamine, diarrhea, nausea, flatulence, abdominal pain, skin symptoms: rash, swelling, itching, atopic lesions, and respiratory symptoms: cough, shortness of breath, and severe cases, even respiratory failure occurs. These symptoms may appear immediately after a meal and several hours or days later.

Lactose intolerance results from the body’s reduced ability to properly break down a compound from another group of nutrients, i.e., lactose disaccharide, into glucose and galactose. It happens due to the reduced level of the enzyme responsible for it – lactase. Undigested lactose begins to ferment in the intestine, which leads to flatulence, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort.

Genetic factors are responsible for the ability to produce lactase, mainly variants of the gene encoding lactase, which determine the level of enzyme activity. In some people, lactase activity is high throughout their life, in some it is lower, and in the remaining part it is high in childhood and then decreases with age.

Symptoms

Symptoms related to lactose intolerance mainly concern the digestive system. Lactose is not absorbed. Unbroken lactose molecules cause water and electrolytes to flow into the small intestine. Bacteria ferment disaccharides in the intestinal flora, contributing to gas formation in the digestive tract.

As a result, lactose intolerance is usually accompanied by abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, and excessive gas secretion. People with adult-type hypolactasia cannot digest disaccharides, so small amounts of dairy products do not cause symptoms.

The enzyme deficiency may be acquired and result from damage to the structure of the small intestinal mucosa in the course of another disorder. Then, in addition to the above-mentioned symptoms, ailments characteristic of the underlying disease also appear.

Symptoms of other systems are rarely present in lactose intolerance. Unlike other types of food hypersensitivities, especially those with an immunological basis, skin or respiratory ailments are not very specific. For this reason, a rash, swelling, or shortness of breath after eating lactose food may indicate a problem of another origin, e.g., an allergy.

Symptoms of lactose intolerance in infants and children are the same as in adults. It should be emphasized, however, that undiagnosed food hypersensitivity in newborns may be a direct cause of dangerous water and electrolyte balance disorders, which sometimes lead to dehydration and even death of the child.

Causes

A lactase deficiency may occur in people with lower levels of this enzyme, resulting in the lack of hydrolysis of lactose into the absorbable components glucose and galactose. There are four primary causes of lactose intolerance.

Primary lactase deficiency is the most common reason for lactase deficiency, also known as lactase persistence. With age, the activity of the lactase enzyme gradually decreases. Enzyme action decreases in childhood, and symptoms occur in adolescence or early adulthood. It has recently been observed that lactase persistence is ancestral, and lactase persistence is secondary to mutation.

Due to infectious, inflammatory, or other diseases, damage to the intestinal mucosa may cause secondary lactase deficiency. The most common causes are:

- Gastroenteritis

- Gluten intolerance

- Crohn’s disease

- Ulcerative colitis

- Chemotherapy

- Antibiotic therapy

Primary disorders of lactase production may occur as congenital alactasia (congenital lactase deficiency) or as adult-type hypolactasia. Congenital alactasia is a rare disease syndrome (several dozen cases have been described so far), manifesting itself in the neonatal period with severe diarrhea accompanied by dehydration and progressive malnutrition, the direct cause of which is the supply of lactose in the diet. Symptoms of the disease result from the lack or low expression of lactase in the limb of the small intestine despite the standard structure of the intestinal mucosa. The disease requires permanent exclusion of lactose from the diet.

Adult-type hypolactasia (hereditary lactase deficiency) is the most common form of genetically determined lactase deficiency. It is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. It appears after the age of 3, most often during adolescence or early adulthood, with standard tolerance of this disaccharide in the earlier period. In this type of intolerance, enzyme production is rarely completely lost.

Diagnosis

Digestive system symptoms that appear after consuming milk or dairy products after allergy has been ruled out may raise suspicion of lactose intolerance. However, the doctor makes the final diagnosis after performing tests to help confirm the diagnosis.

Diagnostics usually include:

- The lactose elimination and challenge test involves following a lactose-free diet until the symptoms disappear (usually about two weeks). If symptoms return after consuming dairy products again, the result of the procedure confirms the relationship between lactose digestion disorder and the occurrence of the sign

- A breathing test assessing the concentration of hydrogen in the exhaled air, which is carried out after consuming lactose

Less frequently, lactose intolerance requires confirmation in more specialized tests, including:

- Determination of stool pH

- Endoscopy

- Study of molecular polymorphism of the lactase gene

Patients are also recommended to be tested for lactose intolerance with, e.g.:

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Chronic fatigue

- Arthritis

Specialists also describe a strong relationship between decreased bone density and hip fractures in postmenopausal women with lactose intolerance. Additionally, the observed calcium levels in these women were lower than in the rest of the population.

Diagnostic Tests

The fundamental test for determining lactose intolerance is the hydrogen breath test. It is a diagnostic tool used in clinical practice to diagnose certain gastroenterological diseases.

Under physiological conditions, hydrogen and methane are not present in exhaled air. Its possible presence indicates that it was produced by bacteria colonizing the colon. In such a situation, hydrogen and, in some situations, also methane are released.

The test begins with measuring the value of hydrogen released on an empty stomach. Then, the selected substance is administered in a strictly defined amount. Depending on the suspected disorder, you can administer.

Measurements of exhaled hydrogen are taken multiple times at various minutes of the test. In patients with slow intestinal transit, an additional measurement is performed 150 and 180 minutes after loading with a given substance. The results are obtained immediately after the test is performed. The gastroenterologist or clinical dietitian interprets them and then makes the diagnosis.

Specialists in diagnosing lactose intolerance use the following tests.

- Stool pH analysis – if the stool pH is acidic, it means food intolerance because undigested lactose causes acidification of the stool

- Elimination trial – involves the patient following a lactose-free diet for two weeks. It is observed whether the symptoms disappear during this period and whether they appear subsequently after consuming this sugar. The test helps confirm the suspicion of lactose intolerance

- Oral lactose administration test – the doctor gives the patient (on an empty stomach) oral lactose and then determines the blood glucose concentration

- Molecular testing of lactase gene polymorphism (LCT) – this type of diagnostics helps to exclude ATH, i.e., hypolactasia in adults

- Endoscopy is one of the most invasive diagnostic methods, but it is also the most effective. During an endoscopic examination, the doctor takes a sample of the small intestine to determine its lactase content

- Blood test – non-invasive and safe test for food intolerance

Treatment

In the case of congenital lactase deficiency, treatment involves permanently eliminating products containing milk sugar from the diet. Patients with congenital lactase deficiency cannot tolerate even small amounts of food containing lactose, and if left untreated, the disease may be life-threatening. Lactase tablets help in the digestion of dairy foods. Consume it before a meal containing milk and milk products.

In the case of primary lactase deficiency, treatment may focus on eliminating products containing lactose from the diet or reducing the amount they consume. If you have congenital lactase deficiency, follow the dietary rules for lactose intolerance throughout life.

In the case of secondary lactose intolerance, therapy includes periodic elimination of products containing milk sugar and, in infants and small children, the use of lactose-free milk formulas.

The specialists recommend following the lactose intolerance diet until the disease that caused damage to the intestinal epithelium is cured (an exception may be, for example, Crohn’s disease). After its regeneration, the symptoms of intolerance should disappear. You can then return to your regular diet.

Diet

In the case of lactose intolerance, you should switch to a lactose-free diet, which means eliminating milk and milk products and products containing lactose. You should also, and absolutely, read the labels on products, even though it would seem that there is no milk in these products.

And although it seems extremely difficult, such a lactose-free diet can be perfected. All the more so because producers increasingly think about people who have problems digesting milk sugar and create lactose-free products, especially for them, or typically milk products that remove problematic sugar.

The diet should be planned under the supervision of a doctor or dietitian. Please remember that eliminating lactose from the diet (mainly dairy products) reduces the body’s absorption of calcium, which in turn may lead to osteoporosis. Therefore, patients diagnosed with lactose intolerance should supplement the deficiency of this element from other food sources.

Lactose-free Products

Many food products contain lactose, including those that may not be associated with milk. Individual product groups differ in the amount of lactose in their composition. Lactose is in dairy products, i.e., cow’s milk, goat’s milk, sheep’s milk, powdered milk, yogurt, buttermilk, kefir, cheese (both white and yellow), cottage cheese, processed cheese, ice cream, and cream. Slightly less lactose is in products, e.g., sweets (especially chocolate), bread and bakery products, breakfast cereals, and ready-made cake mixes.

People with lactose intolerance can use increasingly available products designed with this condition in mind. One such product is lactose-free milk. It has a characteristic, sweet taste. It is sweeter than regular milk because the taste of the sugars into which lactose is broken down during its production is sweeter than the taste of lactose itself.

There are also more and more other lactose-free products on store shelves. We can easily buy, for example, various types of cheese or yogurt safe for lactose intolerance.

Sources

- Lactose: Characteristics, Food and Drug-Related Applications, and Its Possible Substitutions in Meeting the Needs of People with Lactose Intolerance. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9141425/.

- Lactose Intolerance. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532285/.

- Cow Milk Allergy. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542243/.

- Lactose intolerance. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/lactose-intolerance/.

- Symptoms & Causes of Lactose Intolerance. NIH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/lactose-intolerance/symptoms-causes.

- Lactose intolerance. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1906652/.

- Congenital Lactase Deficiency: Mutations, Functional and Biochemical Implications, and Future Perspectives. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6412902/.

- Adult-type hypolactasia and regulation of lactase expression. NIH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15777735/.

- Diagnosis of Lactose Intolerance. NIH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/lactose-intolerance/diagnosis.

- Hydrogen breath test for the diagnosis of lactose intolerance, is the routine sugar load the best one?. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2761582/.

- Treatment for Lactose Intolerance. NIH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/lactose-intolerance/treatment.

- Nutritional management of lactose intolerance: the importance of diet and food labelling. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7318541/.

- Lactose Intolerance and Bone Health: The Challenge of Ensuring Adequate Calcium Intake. NIH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30925689/.

- Advances in Low-Lactose/Lactose-Free Dairy Products and Their Production. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10340681/.