What are the types of aphasia?

Global aphasia is a severe type of aphasia. It affects language processing, making it challenging for the person to communicate and understand others. However, other cognitive not related to speech capacities may remain unaffected. This condition can occur after a stroke or brain injury. There is a chance of improving over time, but there is also a risk of long-lasting damage.

Broca aphasia is a type of partial speech loss. It affects speaking fluency. Individuals have problems communicating and can only say a few words at a time. They can understand other people’s speeches but may struggle with writing.

Mixed non-fluent aphasia involves narrow and challenging phrasing, like in Broca’s aphasia, but with more limited comprehension capabilities. Patients may have fundamental reading and writing skills.

Wernicke aphasia is also known as fluent or sensory aphasia. People with this disorder have problems understanding articulated words but can still speak. Individuals with this condition may have difficulty with reading and writing and experience incoherent speech, often using irrelevant or nonsensical terms.

Anomic aphasia makes it hard to find the right words, leading to communication problems.

Individuals with PPA gradually lose their ability to speak as a result of neurodegenerative conditions affecting the brain. It is typically accompanied by symptoms of dementia and memory loss.

Aphasia – what causes it?

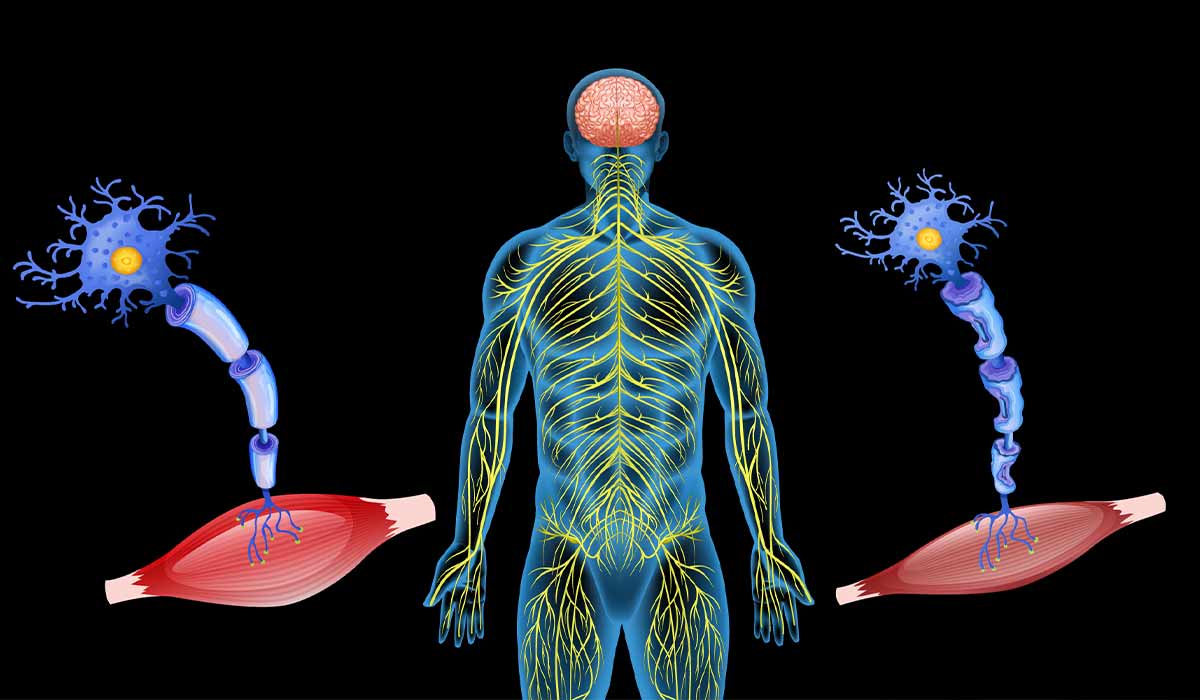

Aphasia develops in humans when there is some damage to structures belonging to the central nervous system. Here, however, it is necessary to emphasize the key aspect. This problem has its roots in defects affecting the brain itself. In people with aphasia a speech apparatus, i.e., tongue and larynx elements work correctly.

Previously, it was believed that aphasia could only be a result of damage to distinct brain regions. These are the so-called speech centers, which are:

- Broca area(in the frontal lobe of the brain);

- Wernicke area(in the temporal lobe of the brain).

It turns out that damage to, e.g., nerve fibers that link these areas with other brain parts can also result in speech disorders.

The condition that usually causes aphasia is stroke. However, it can occur as a result of other conditions, such as:

- head damage

- neuro infection (such as herpes encephalitis)

- neurodegenerative conditions (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease)

- brain tumors

- atherosclerosis of the arteries that deliver blood to the brain.

These are the most standard causes of aphasia. This problem, although much less frequent, may also result from epilepsy (then the aphasia is usually temporary and lasts for a short time).

Aphasia – what are the symptoms?

Aphasia is usually easy to diagnose – speech disorders are usually clearly visible to the patient’s environment and often also to the patient himself. During the problem, there may be signs like:

- considerable difficulty in composing even the most straightforward sentence;

- problems with naming things – it may seem as if the person cannot remember what to call a specific object;

- using uncommon terms in discussions or forming sentences that make thoroughly no sense;

- speaking only single, totally incomprehensible phrases.

However, even if the patient only utters snippets of words, they usually have “in his head” what they would like to say – aphasia is not due to memory problems or intellectual disabilities but is simply a speech disorder.

Aphasia in children

Aphasia is a speech disorder that can only be diagnosed in patients whose speech has already developed and lost due to an incident. It cannot happen in a child who is still developing speech.

Among speech therapy diagnoses, there is developmental aphasia(dysphagia) in children. The reason for this may be birth injuries, encephalitis, or other injuries that occurred before speech development but are not the result of hearing impairment or mental disability.

Developmental aphasia is manifested by:

- difficulties in understanding speech and creating statements,

- indistinct articulation,

- difficulty finding words and building sentences.

Another type of aphasia diagnosed in children is acquired aphasia. We are dealing with it when the child’s speech develops properly until the moment of brain damage, and then symptoms of speech formation and development disorders appear. Acquired aphasia is diagnosed at the earliest in the second year of life because during this period the child begins to formulate his utterances, as well as to understand the words of others.

The most common causes of acquired aphasia in kids include:

- injuries,

- inflammatory and degenerative diseases,

- hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke.

Unlike adult aphasia, childhood aphasia can occur with similar frequency after both left and right hemisphere damage. Aphasia in adults after damage to the right hemisphere is very rare.

Unless there is damage to both hemispheres, the symptoms of childhood aphasia disappear much faster than in adults. The younger the child, the sooner they can return to fluent speech.

What are other speech disorders in children?

Every kid grows at their own pace. When should you be concerned? There are some situations, e.g., if a kid’s speech does not improve or if they have trouble learning and using new phrases. When this problem occurs, consult with a pediatric speech therapist so the specialist can determine the reason for this issue.

The most typical speech conditions in youngsters include:

- Stuttering– regular repetition or prolongation of sounds, syllables, words, and pauses that disrupt the speech rhythm. Stuttering comes from abnormalities and tensions in the mouth – the child may have problems with the process of “inhaling, exhaling” and with the tension of the vocal cords or muscles in the mouth. It is natural for children up to the age of 5, but if it does not pass, it is worth going to a specialist for advice.

- Lisping– is divided into labiodental and interdental. The child incorrectly pronounces dentalized sounds, i.e., those in which the proper arrangement of the teeth plays a significant role in vocalization. It is worth paying attention to lisping during the period when the child’s milk teeth fall out and permanent teeth grow in. Changes in the teeth can affect speech, but if an eight-year-old still has problems pronouncing these sounds, you should start classes with a speech therapist.

- Dysarthia– consists of incorrect articulation caused by disorders of the speech apparatus, rarely occurs in children, and is manifested by slurred speech, difficulty understanding, excessive salivation, and difficulty in eating.

- Selective mutism– is an anxiety disorder. The first symptoms appear between two and five years of age as a child’s silence in various situations. The toddler understands speech but does not want to talk themself – they may not speak to teachers or peers at all or speak only to selected people. Selective mutism requires psychological consultation.

- Paraphasia– in this speech disorder, the child speaks fluently but twists words – and uses similar words with the wrong meaning. In practice, it can omit sounds or add them to words, resulting in even new words that have no meaning.

- Aphonia– it is a loss of sonority of the voice, otherwise voicelessness. As a result of the disease usually lasts up to 2 weeks. It is relatively rare in children but more common in adults who work with the voice (e.g., teachers).

- Alalia– occurs as a result of damage to the cortical structures of the brain, often as a result of perinatal injuries or as a result of encephalitis and meningitis. In children affected by the disorder, speech does not develop until 6-7 y.o. In addition to speech disorders, the child is motor and intellectually fit. The basis of alalia’s treatment is working with a child psychotherapist and a speech therapist.

- Bradylalia – it is the slowness of speech. Speech is very slow, there are long pauses between words, and the speech tone is monotonous.

- Tachylalia – is talking too fast. Within a second, even 20-30 sounds may appear, but utterances are accompanied by dropping some syllables and rearranging them. Speech is quick and very slurred.

What does the diagnosis of aphasia look like?

The occurrence of aphasia – particularly sudden – should always be consulted with a specialist.

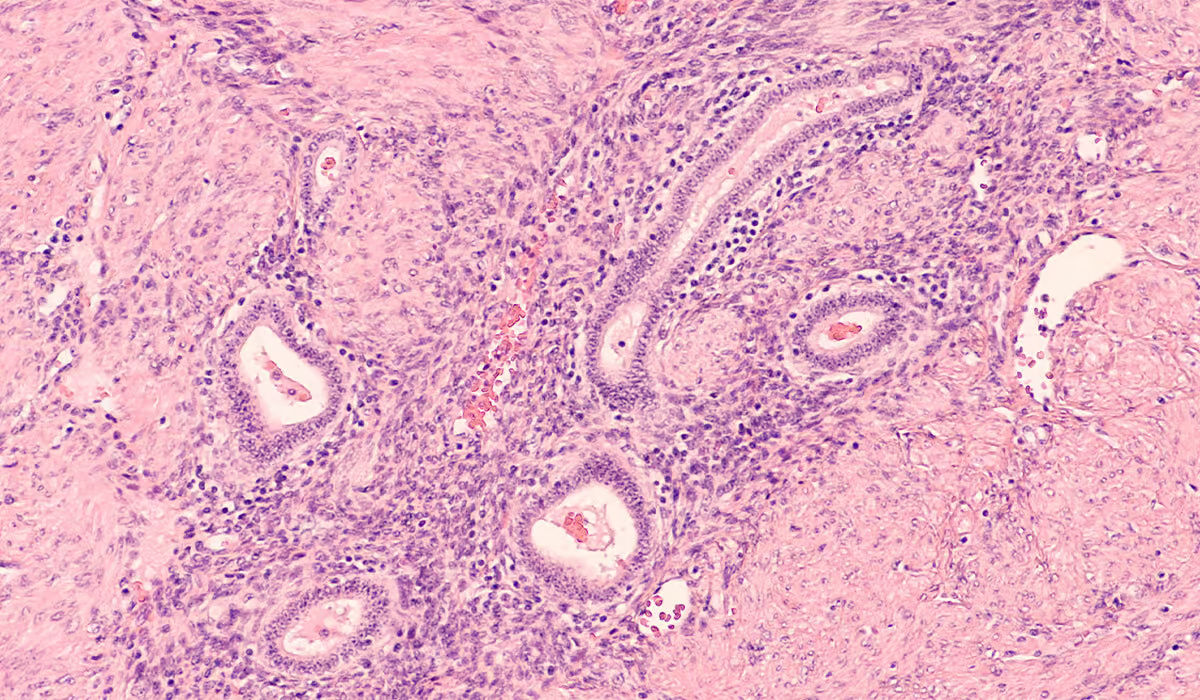

Diagnosing aphasiainvolves a combination of techniques. The doctor starts with questioning about your medical history and physical examination. Then there may be a need for diagnostic imaging and laboratory testing. Depending on the circumstances, the specialist can propose multiple tests to eliminate other potential disorders or causes that exhibit comparable symptoms to those associated with aphasia.

In the event of aphasia, the patient first undergoes a neurological examination – other abnormalities detected during the examination (such as, for example, sensory disturbances or paresis) may suggest what exactly the patient suffered from or which part of his brain was damaged.

Later, imaging tests of the head are usually ordered, such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging – these make it possible to identify, for example, foci of ischemia within the brain or the presence of an intracranial tumor in the patient.

To confirm if someone has aphasia and determine the best language treatment, a speech-language pathologist can conduct a thorough language assessment. This assessment assesses if the person can:

- name everyday objects,

- hold a discussion,

- understand and use terms accurately,

- respond to questions about something they read or heard,

- repeat phrases and sentences,

- follow instructions,

- respond to yes-no and open-ended questions on typical issues,

- read and write.

Aphasia – how to treat it?

Aphasia itself is not a condition but a manifestation. Treatmentmust concentrate on its cause. In the case of people who have experienced a stroke, along with the general improvement of their condition, speech disorders may also subside.

However, the improvement in this case may be of varying degrees – in some patients, the aphasia disappears entirely, while in others the problem persists all the time. Speech training is significant for many patients, as it is often possible to reduce the degree of speech disorders that they have – with the participation of a speech therapist.

The aphasia treatment in people who developed it in connection with a brain tumor is different. In their case, effective therapy, based on, e.g., removal of the entire lesion, sometimes turns out to be a sufficient method of treatment. The tumor may compress the speech centers in the brain, and its resection, eliminating this compression, leads to the aphasia disappearing.

Aphasia – prognosis. Can aphasia be reversed?

Just as aphasia impacts the quality of life, it does not affect the survival of patients. However, the exact prognosis of individuals who have aphasia cannot be determined – it all depends on what caused this issue.

The general prediction is better for those with easily treated neuro infections and worse for the ones with aphasia due to a very malignant brain tumor.

What can I do for myself if I have aphasia?

Aphasia causes significant life changes. Perhaps you feel frustrated, nervous, impatient, sad or scared. It is challenging for you to convey what you feel and think. This reaction is natural. Living with aphasia is not easy. Thus, it is worth doing everything possible to improve its quality.

Attend a speech therapist for speech rehabilitation therapy to improve your communication skills.

Use psychological support. Psychotherapy will strengthen your emotional resources so that you can face new challenges.

Do not avoid physiotherapy classes. Thanks to them you will be able to improve your motor skills.

Involve your loved ones. Their support can help you to adjust to the new circumstances.

Be patient with yourself. Healing is a slow process. Remember that in the vast majority of cases, progress can be seen even many years after developing aphasia.

Develop your way of communicating so that other people can understand what you want to say. Sometimes, for example, articulating slowly or repeating your words helps. Use gestures, drawings, or write what you want to express.

Try to do some calming activities. It could be painting, singing, gardening, or cooking.

Someone close to me has aphasia – how can I help them?

Patients with aphasia may react in various ways: anger, sadness, despair, fear, frustration, or shame. It’s natural for them to feel like a different person than they used to be. After all, their lifestyle is radically changing. They may not understand what has happened to them or how they will cope with the changes they face.

In turn, people close to the patient may not know how to react and what to do. In many cases, they make typical mistakes: they ignore the patient, talk to them like a child, and speak for them. In short, they do what they think is most reasonable to support but they don’t recognize that it can be frustrating for the patient.

How can you help a loved one with aphasia? Treat them with respect and as an adult, not a kid. Involve them in everyday discussions and decision-making. Encourage as much autonomy as possible. Give the individual with aphasia time to answer, help them express themselves, and talk naturally about what they feel. Give support when they need it and help them seek professional help.

Knowing that there is someone you can always count on is as important as speech therapy and psychological therapy. Working on aphasia is a long-term process that requires patience.

Sources

- Aphasia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559315/.

- Aphasia. NIH. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/aphasia.

- Aphasia after stroke: natural history and associated deficits. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1028640/.

- Language reorganization patterns in global aphasia–evidence from fNIRS. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9853054/.

- Broca Aphasia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436010/.

- Atypical clinical features associated with mixed pathology in a case of non-fluent variant primary progressive aphasia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6759324/.

- Wernicke Aphasia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441951/.

- Anomic aphasia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/medgen/312.

- Primary progressive aphasia. GARD. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/8541/primary-progressive-aphasia.

- Neuroanatomy, Broca Area. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526096/.

- Neuroanatomy, Wernicke Area. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK533001/.

- Aphasia. NIH. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/aphasia.

- Aphasia. NIH. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/health/voice/Aphasia.pdf.

- Aphasia in children. NIH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2420691/.

- The Neuropathology of Developmental Dysphasia: Behavioral, Morphological, and Physiological Evidence for a Pervasive Temporal Processing Disorder. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3167171/.

- Stuttering. NIH. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/stuttering.

- The sociolinguistics of lisping: a review. NIH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32646249/.

- Dysarthria. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592453/.

- Selective Mutism. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2861522/.

- Describing Phonological Paraphasias in Three Variants of Primary Progressive Aphasia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6111492/.

- Aphonia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh?Db=mesh&Cmd=DetailsSearch&Term=%22Aphonia%22%5BMeSH+Terms%5D.

- Alalia. APA. https://dictionary.apa.org/alalia.

- Bradylalia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/medgen/548643.

- Tachylalia. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/medgen/1671016.

- Aphasia. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/aphasia/treatment/.

- The Prognosis for Aphasia in Stroke. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3117986/.

- Aphasia: What Is, Symptoms, Dangerous Causes, and Treatment

- What is Aphasia?

- Aphasia – what causes it?

- Aphasia – what are the symptoms?

- Aphasia in children

- What does the diagnosis of aphasia look like?

- Aphasia – how to treat it?

- What can I do for myself if I have aphasia?

- Someone close to me has aphasia – how can I help them?