Typically, anorexia begins in young girls during puberty or in young women, most often between the ages of 14 and 18, on average at the age of 15, with a currently observed tendency to lower the age of life at the time of onset of the disease. This disorder involves the patient engaging in numerous deliberate actions to lose or maintain a low body weight, with a body weight at least 15% below the expected norm for age and height or body mass index (BMI). During the disease, disturbances in the perception of one’s body image and somatic, metabolic, and neuroendocrine disorders occur.

Symptoms

The goal of a patient with anorexia is to reduce body weight and then maintain it.

The patient constantly limits the amount and frequency of meals, restricts the diet, and avoids the so-called fattening foods with a high caloric index; additionally performs at least one of the following activities – uses exhausting physical activities, takes hunger suppressants, causes vomiting, uses laxatives or diuretics.

There is a disturbed image of one’s own body. The individual perceives it as “still too fat” and is also accompanied by a worry of gaining weight.

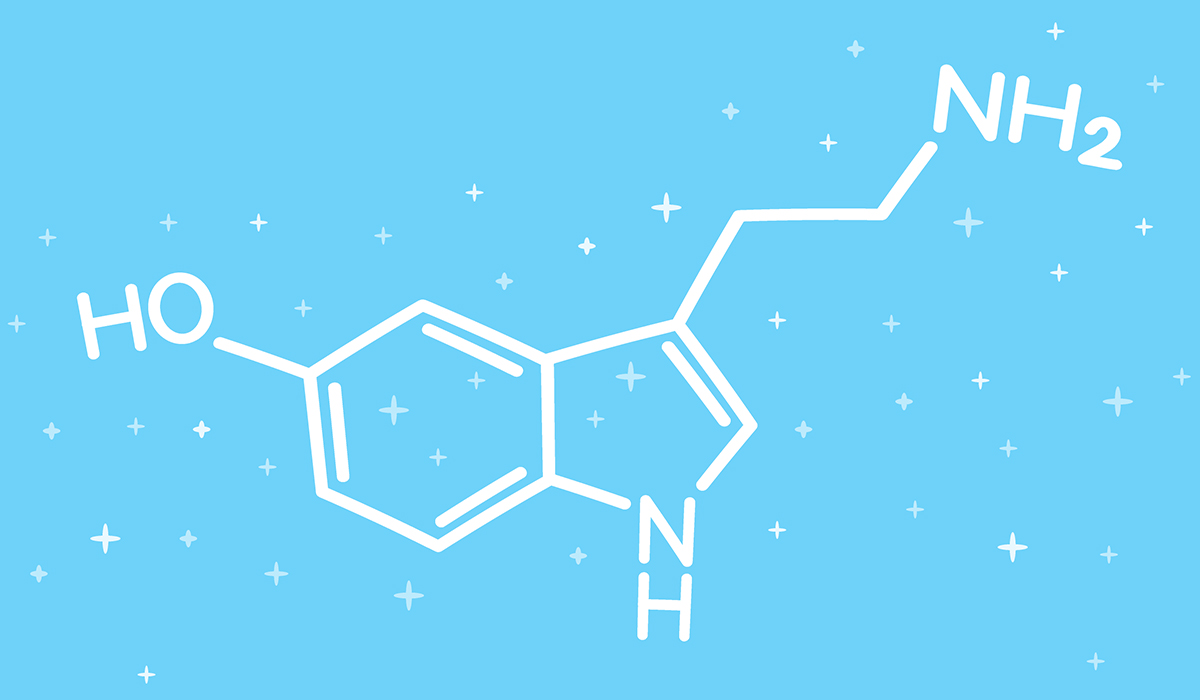

The patient develops hormonal disorders in the field of the so-called hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and gonads, which in women leads to amenorrhea (before puberty) or cessation of menstruation (after puberty), and in men to potency and libido disorders. Other hormonal conditions that may appear include abnormal levels of thyroid hormones, growth hormone, and insulin.

Hormonal conditions may be accompanied by numerous additional somatic ailments and abnormalities, including:

- Muscle atrophy

- Swelling

- Paleness

- Dryness and flaking of the skin

- Lowering body temperature

- Hair will fall out

- The appearance of characteristic hair on the body in the form of fuzz (lanugo)

- Lowering blood pressure

- Decrease in heart rate

- Heart arrhythmia

- Fainting

- Headaches and dizziness

- Constipation

- Flatulence

- Inflammation of the gastric mucosa

- Anemia

- Swelling of the salivary glands and tooth decay (resulting from severe vomiting)

Anorexia should also be differentiated from some somatic diseases, especially those related to the gastrointestinal tract and neurohormonal disorders.

Anorexia may also be accompanied by symptoms of mental disorders, including:

- Depressed mood

- The decreased joy of life

- The feeling of lack of meaning in life

- Thoughts of suicide

- Tension

- Irritability

- Sleep disorders

- Symptoms of obsessive thinking and compulsive behavior

Anorexia undoubtedly requires treatment because as it develops, it leads to severe somatic and mental disorders. It is essential to observe its symptoms as early as possible, make a correct and professional diagnosis, and initiate treatment.

However, catching a patient’s symptoms of this disorder early is sometimes challenging. Anorexia usually begins with the desire to “lose a few kilos” – with a variety of different reasons and different patient motivations. Initial weight loss successes give a control sense over the body and life, improve mood, and motivate to limit food intake further.

The patient most often does not notice the period when – while maintaining control over the ways of restricting eating “at all costs” – they begin to lose overall control over their own life, the mechanisms of addiction begin to develop and the patient starts to organize their entire life around eating. They absorb information, read guides and books on the subject, watch TV programs on “healthy eating”, and sometimes willingly cook for others but do not eat these meals themselves.

They feel that they are doing “right,” “reasonable,” and sometimes even that they are “doing it for their health.” Counts the calories contained in meals, avoids “fattening” and high-calorie foods, limits the consumption of fats and carbohydrates, and over time, significantly below the accepted standards. Also, the patient’s relatives do not notice the developing eating disorders in the initial period, and, like the patient, they are convinced that this is a suitable or possibly “harmless” approach to eating.

Over time, when the patient’s family notices the problem, the patient begins to “hide” that they limit their eating. They may claim to “eat” alone when in reality they throw away food. Eating restrictions are becoming more severe – the patient continues to reduce the amount and calorie content (and therefore the nutritional value) of meals, which satisfies them. At the same time, they increasingly underestimate the “weight limit” they are trying to achieve. Anorexia may have a wave-like course with periods of greater or lesser restriction of eating, or, as already mentioned, it may also involve bouts of excessive or “normal” eating, followed by vomiting or the use of laxatives.

A person with anorexia often checks how much they currently weigh, anxiously accepting even a minimal increase in this range and with satisfaction with further weight loss (or periodically maintaining a low body weight at a certain level). Sometimes, to lose the “calories consumed”, they use long-term, exhausting, strenuous physical exercises, e.g., walking at a fast pace, even several hours a day.

In the course of anorexia, the perception of one’s body image is also disturbed – the patient, looking at their body, constantly has the impression that there are places in it where they are “too fat,” e.g., they ate yesterday or even just now. It translates the consumed calories into “excessively” fat tissue even though the body is already significantly emaciated or destroyed. It is accompanied by a constant “fear of gaining weight,” sometimes even after eating minimal food portions.

As already mentioned, even the patient’s closest relatives find it difficult to notice the first symptoms of anorexia. It is usually seen when the body is already at a significant level of exhaustion and repeated behaviors leading to eating restriction, such as refusal to eat meals together or in general. But even then, the family often doubts whether such a condition requires professional help or is just a “transitional period” in the patient’s life.

Who May be Affected by the Problem?

Psychopathological symptoms of anorexia include a disturbed image of one’s appearance, fear of obesity, and body distortion despite a significant, visible lack of body weight. Statistically, anorexia is more common in young girls during puberty, boys – before puberty, young and mature women (up to menopause), and young men.

Gender and age are the main determinants of eating disorders that appear in adolescence. Gender is inextricably linked to a social role that has developed over hundreds of years and which further determines certain specific patterns of behavior. During adolescence, mainly girls are exposed to incorrect self-perception, which does not exclude maturing boys from this group.

The predominance of the potential incidence of eating disorders in young women is due to the following factors:

- During adolescence, the body changes, and the “hormonal storm” causes mood swings and increased sensitivity to external stimuli (there is a tendency for the environment to have a tremendous influence on the teenager’s behavior)

- According to physiology, there is an increase in fat tissue (an often misunderstood natural change), and with it, the fear of manifesting obesity.

- The need for competition (although biased in boys) also appears in young girls

- Determinants of a grander and faster need to lose weight

- Changes in the emotional sphere related to the adoption of new social roles, growing expectations, and a constant preference for the opposite sex

- Media trends of slim figure

- Fashion presented by “skinny” models

- Photo sessions surrounding the background of urban life (billboards, advertisements, women’s magazines) distort the image of the female figure.

- The impact of retouching programs and filters

- Constant “fight” in shaping beauty standards, combined with low knowledge and nutritional education, cause permanent changes in the psyche of maturing youth.

- Misinterpretation of body signals and growing up in the shadow of complexes

Risk Factors

Risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing the disease are personality traits like:

- Self-confidence

- Unstable self-esteem

- Inability to make decisions

- Tendency to translate emotions

- Low-stress resistance

- Perfectionism

- Social maladjustment

- Ambivalence

- Strong need for achievement

The risk factors also include:

- Unpleasant experiences, or events (related to violation of self-esteem, self-dissatisfaction, stress)

- Family situation (low family cohesion, conflicts, increased parental control, limited autonomy, change of environment, addictions – alcoholism, drug addiction)

- Broadly understood socio-cultural expectations (comments about appearance, body, observation of weight loss behaviors in friends)

- Performing a profession that requires maintaining an impeccable figure

- Victims of sexual abuse

Treatment

Even if the first disturbing thoughts about a person’s health appear, it is worth motivating them to seek a psychiatric and psychological consultation. People professionally dealing with the treatment of eating disorders will perform a complete diagnosis and, if anorexia is diagnosed, they will propose appropriate treatment.

Unfortunately, a person whose loved ones suspect an eating disorder usually does not want to agree to such a consultation, believing that they “eat healthily” and “nothing is wrong.” A psychiatric consultation of an adult suspected of anorexia cannot be carried out without their consent, except for an advanced form of anorexia with co-occurring symptoms of other mental disorders/diseases (e.g., severe depression with suicidal thoughts or an ongoing psychotic process) and a threat to the patient’s life.

Treatment of anorexia should be comprehensive and long-term, including psychological aspects and psychiatric and somatic symptoms associated with this disorder.

Treatment demands a unique approach to each patient. It is usually based on psychoeducation and psychotherapy, which aims to, among other things, change the way of thinking, behavior, and eating. In more advanced forms of anorexia, this procedure is combined with behavioral eating training under hospital conditions.

Sometimes, when other symptoms of mental disorders co-occur, e.g., depression or anxiety, additional pharmacological treatment should be implemented. Periodic check-ups with a family doctor or internal medicine doctor are also necessary to fully assess the somatic health condition, and possibly consultations with doctors of other specialties, including a gynecologist, endocrinologist, gastroenterologist, or dentist. In the case of severe somatic disorders in which outpatient treatment is not acceptable (e.g., circulatory system disorders, severe water and electrolyte disorders), hospitalization in departments, e.g., pediatrics, internal medicine, or intensive care unit, is recommended.

Treatment for patients with anorexia nervosa takes years rather than weeks or months. Patients must accept the need to achieve normal body weight. Treatment limited to nutritional therapy alone is associated with the risk of recurrence. The effectiveness of anorexia treatment should be monitored by weighing the patient so that body weight measurement does not become a battleground for the patient.

It is necessary to involve the family in the treatment process (especially in the case of minor patients) so that while supporting the patient, they act with gentle firmness and assertiveness. An essential aspect of therapy is the psychoeducation of the patient and the family – explaining the mechanisms of anorexia and basic ways of coping with the disease, with an attempt to raise awareness of the psychological mechanisms of the disorder.

It is crucial to manage the possible somatic consequences of anorexia – e.g., correcting fluid and electrolyte deficiencies and cardiac disorders. In the case of a life-threatening condition, hospitalization in an internal medicine ward rather than a psychiatric ward is probably more optimal.

Outpatient Treatment

Another approach is outpatient treatment, with temporary acceptance of low body weight, provided that it is stable and constantly monitored, and the patient or their family takes responsibility for appropriate nutrition. In the case of the described procedure, the weight gain is slower but more lasting. However, in the event of a life-threatening condition or significant underweight, it may be necessary to admit the patient to the hospital.

Psychotherapy

Long-term and psychological treatment is recommended, including psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral methods, a systemic approach, and motivational techniques. These interventions should be conducted in conditions that take into account the need to monitor physiological parameters and the somatic treatment of patients. Therefore, cooperation between various specialists is necessary.

The basic principle of its strengthening is psychoeducation and striving to understand the problem, not fighting the patient’s ambivalent attitude toward a cure. Appropriate motivation of the patient is an absolute condition not only for starting therapy but also for its continuation.

Psychotherapy may include individual and group sessions and – in the case of minor patients – work with the family.

Drug Therapy

Pharmacotherapy for anorexia is mainly symptomatic – for example when depressive symptoms co-occur, antidepressants are used.

Sources

- Anorexia Nervosa. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459148/.

- Eating Disorders: About More Than Food. NIH. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/eating-disorders.

- Eating Disorders. NIH. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders.

- Amenorrhea in anorexia nervosa. Neuroendocrine control of hypothalamic dysfunction. NIH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7920581/.

- Reproductive issues in anorexia nervosa. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3192363/.

- Severity of somatic symptoms in outpatients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. NIH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30318829/.

- Anorexia Nervosa. MSD MANUAL. https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/mental-health-disorders/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa.

- Physical Activity in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7019575/.

- The relationship between risk of eating disorders, age, gender and body mass index in medical students: a meta-regression. NIH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30430465/.

- Risk Factors for Eating Disorders. NEDC. https://nedc.com.au/eating-disorder-resources/find-resources/show/issue-39-risk-factors-for-eating-disorders.

- Anorexia nervosa: Outpatient treatment and medical management. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9048449/.

- Psychological Treatments for Eating Disorders. NIH. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4096990/.

- Treatment – Anorexia. NIH. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/anorexia/treatment/.